The Youth Are Disabled (But So Are You)

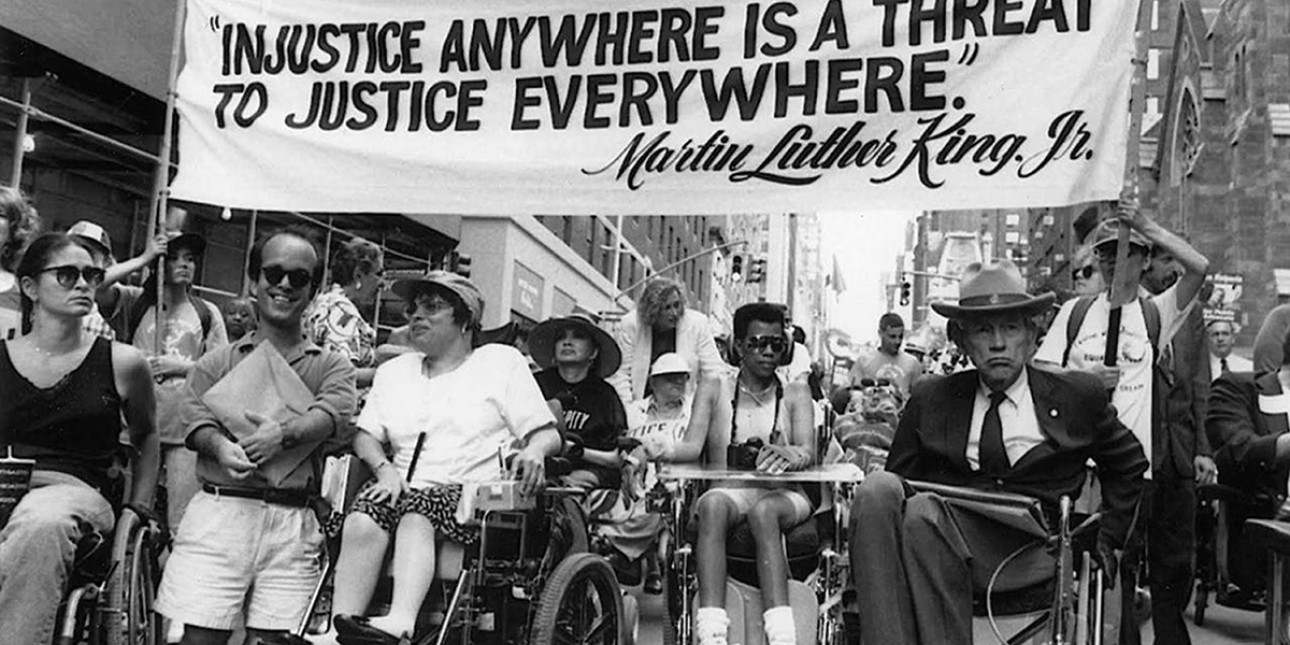

Photo: "The Disability Independence Day March," New York City Civil Rights History Project

Throughout July we celebrate Disability Pride Month, a celebration originating in 1990 when the American Disabilities Act was passed. This piece of anti-discrimination legislation was the culmination of an ongoing Disability Rights Movement that coincided and connected with similarly revolutionary movements in the 1960s such as the Black Power Movement, American Indian Movement, Gay Liberation Movement, and Women's Liberation Movement. This era of social activism across a multitude of communities and identities was no coincidence, evidenced by the constant solidarity displayed in between the oppressed. Intersectional solidarity has clearly elevated the cause for disability rights before, but what does that look like for us now in our current landscape of Disability Justice? More specifically to our work, how does this inform how we empower youth?

What does Disability look like?

Before we talk about allyship with the disabled, let's talk about disability! Disability as defined under the ADA is "a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity." That is the definition most people work off of-that disability is something deficient, less than normal, requires "fixing", and an individual responsibility. This framework is called the Medical Model of Disability and is what shapes accessibility laws like the ADA. Disability Justice offers the framework of the Social Model of Disability, one that defines disability as barriers created by systemic inequity.

The example that I use the most to explain this model to folks goes as such:

Imagine we live in a world that is exactly the same as ours, with the exception that everyone flies but you. At first it's fine. Elevators, escalators, and stairs exist, so it's just the same life you've been living, but then they remodel a government building with none of those things, only platforms that fliers can land on. In this scenario, are you deficient? Or are you just knowingly overlooked by the system?

When you think of things that disable people, what can you think of? Oftentimes we can point to things like stairs, uneven sidewalks, and narrow hallways as barriers for some folks with more apparent disabilities such as needing a wheelchair, walker, or cane. An increased focus on mental health means we can also now identify things like loud spaces, bright/colorful lighting, and proximity to crowds as potential barriers for folks with sometimes less apparent cognitive, neurological, or emotional disabilities.

As a disabled youth, I'd like to name some of the things that I find most disabling, for me and my peers: unstable income that leads to unstable food and shelter access, social support nets that don't see us as worthy of sufficient care or learning, and communities that emphasize space and time for work rather than space and time with my loved ones. To adapt the original ADA definition of disability, these kinds of barriers substantially limit one or more of our major life activities. Moreover, you might notice that these barriers aren't just limited to what "traditionally" disabled youth face-these are all things any of us can face, because youth are disabled by the system. Specifically, I tried to describe the issues Youth Collaboratory focuses on—youth and young adult homelessness, interpersonal and commercial sexual violence, and building community—because I see these as ways that we discover how to empower youth, rather than just ways we can define youth disempowerment.

What does Accessibility look like?

So how do we move towards being a system that creates accessibility for the disabled youth that we serve? It starts by grounding us in two important truths.

Firstly, as arbiters of the system's will, we are inherently part of the problem and in a position of power over our youth. We exist as youth support services in order to create a shift of power with our youth with the goal of giving power to our youth.

Secondly, the problems youth face are intertwined because they often come from the same root. Youth services, in the diversity of sectors that exist, are often siloed as if needs can be tackled one at a time. Take for example again youth and young adult homelessness, interpersonal and commercial sexual violence, and building community. Would as many youth experience homelessness if they could establish a feeling of safety and security or understood how to build healthy community? Would youth be subject to interpersonal and commercial violence if they had places to live and people to ask for help? Would youth be isolated from community if they were in cities and neighborhoods that prioritized sharing spaces with each other or modeled ways to navigate healthy conflict?

It is daunting to imagine the path that leads us through these issues but it is not new for us to have done this. We can find inspiration in pre-colonial communities, Black and Queer interventions in 1900s America, COVID-19 mutual aid networks, and more that all showed disabled people as part of-rather than less than-community. Maybe most importantly these models show us that the work of pulling people into community doesn't happen without working with those people and having them lead.

The ADA set a bare minimum for accessibility, one that still shuts disabled people out of community, but one that we can rise above by being imaginative in the ways that we can radically care for and be in relationship with each other. This Disability Pride Month I invite y'all to join me in celebrating the ways disability and disabled communities lead us to discover how we build communities that make space and time for us all.

Resources/Further Reading

- Beyond Ramps: Disability at the End of the Social Contract by Marta Russel

- Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

- The Right to Maim by Jasbir Puar

- Leaving Evidence, a blog by Mia Mingus

- The Disability Visibility Project, an online community founded and directed by Alice Wong

Author Bio: bri is a community organizer on occupied Powhatan land in so-called Richmond, Virginia. Guided by the principles of abolition, decolonization, and Healing Centered Engagement, bri builds support networks grounded in community and mutual aid. Their lived experience of being a queer & trans, Mad & disabled, brown Filipino immigrant enables bri to leverage their knowledge into their grassroots organizing, nonprofit consulting, and participatory action research. bri's work aims to bring more oppressed voices and perspectives into crucial discussions about policy and accessibility through the development of better cross-systems collaborations, building a future where everyone can pursue joy.